My friend Craig put me onto Steven Johnson’s The Ghost Map: The Story of London’s Most Terrifying Epidemic – and How It Changed Science, Cities, and the Modern World.

My friend Craig put me onto Steven Johnson’s The Ghost Map: The Story of London’s Most Terrifying Epidemic – and How It Changed Science, Cities, and the Modern World.

Cholera devastates cities, a lethal enemy that, through the centuries, killed millions. The Ghost Map takes us to 1854 when a cholera epidemic ravaged London’s Soho district, and claimed more than six hundred lives. The death toll would have risen higher had not many anxious citizens fled.

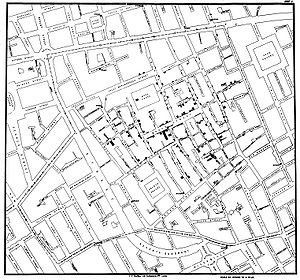

The dominant epidemiological paradigm of the day designated cholera an airborne disease, the product of foul air associated with overflowing cesspools and unsanitary living conditions. For several years prior to the outbreak, Dr. John Snow, a renown anesthesiologist, suspected the airborne theory wrong. When fatalities in Soho began to multiply, he courageously entered the area to test an alternative explanation. By a process of rigorous neighborhood interviews, he developed a map of the district that showed where fatalities occurred (see the map below), visually demonstrating a pattern that linked the disease to a water pump on Broad Street.

Many members of the medical establishment were critical, even hostile, to Snow’s waterborne theory. At first, Snow found no support from the Rev. Henry Whitehead, an Anglican clergyman who indefatigably ministered to the sick and dying, while at the same time, undertaking his own investigations into the causes of the disease. As he ministered to afflicted families, he determined that most, if not all, had drunk from the Broad Street pump. His careful study of Snow’s research and his own intimate knowledge of the neighborhood led him to embrace the waterborne theory. By an exhaustive study of death records, he determined the index case of the outbreak.

The efforts of Snow and Whitehead were sufficient to persuade the local council to remove the pump. Over a period of years Snow’s theory won over the entire medical and public health establishment. In one of the remarkable engineering feats of history, London constructed a sewer system, which along with the simple precaution of boiling suspect water, brought an end to cholera epidemics in the city.

Problem solvers will love this book. Refusing to submit to the reigning cholera model, two men fought not only the disease but public health officials who were nearly blind to contrary evidence. Correlation was often confused with causation. For example, it was argued that cholera seldom strikes people living on a hill because the air is cleaner at higher altitudes. In fact, people on hillsides were less likely to frequent water supplies contaminated by human waste. At one point, convinced that cholera was spread by the bad air emerging from cesspools, the city shut down thousands of cesspools, and arranged a disposal system that dumped human waste directly into the Thames River, London’s source of drinking water. The author points out that modern bio-terrorists could not have concocted a more efficient plan for spreading the disease. The book reminds me how easy it is to examine a problem, collect facts, and then assign causation where it doesn’t belong. The outcome of fallacious reasoning can be costly, even deadly.

Listen to the author tell the story:

The Ghost Map: