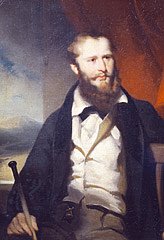

No fiction writer could have created the story of Englishman James Holman (1786-1857).

At age thirteen, Holman joined the British Royal Navy and traveled to North America. For much of the remainder of his life he was on the move, never more happy and healthy than when traveling, even after he went blind In his mid-twenties.

Disability did not dampen his enthusiasm for life. He studied medicine and literature at the University of Edinburgh, committing large bodies of materials to his capacious memory. Obtaining a machine used by British soldiers to write in complete darkness, he cultivated his considerable skills as a writer.

Eventually, Holman set off to explore the world. By his death he was the most traveled man in history. Preferring to journey without companions, he visited every inhabited continent. Money was scarce, but he found ways to stretch his funds and keep on moving. He walked, became a skilled horsemen, and accepted rides in coaches, ships and wagons, often journeying with strangers who did not speak English. Nevertheless, he learned to communicate, ask questions, and listen. His sensitivity to sounds and smells was extraordinary. And he wrote and wrote, his travel narratives becoming a stunning literary achievement.

Remarkable determination and fortitude drove him to places few went voluntarily, like Siberia. Holman made the trip by wagon across the bone-jarring, icy roads. He fought to keep his hands from frostbite; the loss of touch would be, for him, a second blindness.

Without sight, his other senses became acute. While riding on horseback in Africa he commented on the beauty of the coconut trees. His companions looked in vain to see them – until they traveled round the bend in the road and there it was, the grove Holman smelled!

When the British tried to establish a post off the coast of what is now Equatorial Guinea, the captain of the ship used Holman to establish a relationship with the area’s tribal chieftain. At first they did not share a single word in common, but Holman learned to communicate, and came to understand the structure and values of the tribe. He proved an indispensable adviser to the captain.

Long before the benefits of regular exercise were taken for granted, Holman would take a rope, tie it to a stage coach or wagon, and run behind it. He kept himself fit.

When Holman sensed his death was imminent, he wrote his autobiography, finishing it one week before he died. Sadly, his last manuscript is lost, probably forever.

Winston Churchill once urged a group of schoolboys: “Never, never, never give up.” The Blind Traveler never did. Overcoming seemingly insuperable obstacles, he ranks among those 19th century explorers and adventurers who helped western nations obtain a better understanding of the world.

Jason Roberts tells well Holman’s story of inspiring courage and endurance in A Sense of the World: How a Blind Man Became History’s Greatest Traveler.